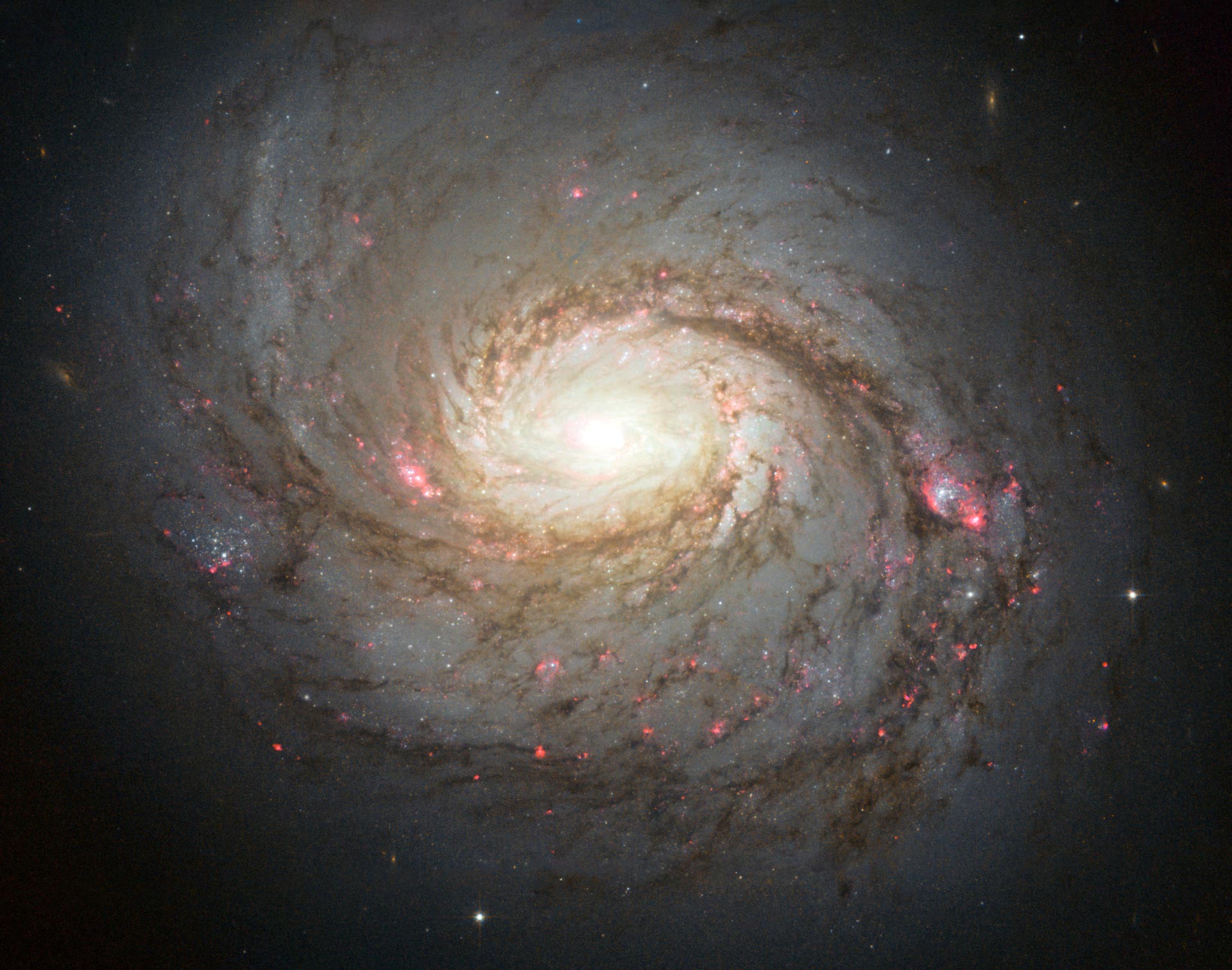

Imagen del Hubble de la galaxia espiral NGC 1068. Crédito: NASA / ESA / A. van der Hoeven

Un equipo internacional de científicos descubrió por primera vez evidencia de una emisión de neutrinos de alta energía de la galaxia NGC 1068. NGC 1068, también conocida como Messier 77, se observó por primera vez en 1780. galaxia activa En la constelación de Cetus es una de las galaxias más famosas y mejor estudiadas hasta la fecha. Esta galaxia se encuentra a 47 millones de años luz de nosotros y se puede ver con un telescopio grande. Los resultados se publicarán hoy (4 de noviembre de 2022) en la revista CienciasAyer participó en un webinar científico que reunió a expertos, periodistas y científicos de todo el mundo.

Los físicos a menudo se refieren a los neutrinos como una «partícula fantasma» porque nunca interactúan con otra materia.

El descubrimiento se realizó en el Observatorio de Neutrinos IceCube. Este enorme telescopio de neutrinos, impulsado por la Fundación Nacional de Ciencias, incluye mil millones de toneladas de hielo procesado a profundidades de 1,5 a 2,5 kilómetros (0,9 a 1,2 millas) por debajo de la superficie de la Antártida, cerca del Polo Sur. Este telescopio único explora los confines más lejanos de nuestro universo utilizando neutrinos. Informé la primera observación de un Una fuente de neutrinos astrofísicos de alta energía En 2018. La fuente es un conocido blazar llamado TXS 0506 + 056 ubicado a 4 mil millones de años luz del hombro izquierdo de la constelación de Orión.

Un solo neutrino puede determinar la fuente. Solo observar múltiples neutrinos revelará el núcleo misterioso de los objetos cósmicos más energéticos, dice Frances Halzen, profesora de física en la Universidad de Wisconsin-Madison e investigadora principal en IceCube. «IceCube ha recolectado alrededor de 80 tera-electronvoltios de neutrinos de NGC 1068, que aún no es suficiente para responder a todas nuestras preguntas, pero sin duda es el próximo gran paso para lograr la astronomía de neutrinos», agrega.

Cuando los neutrinos interactúan con partículas en el claro hielo antártico, producen partículas secundarias que dejan un rastro de luz azul a medida que viajan a través del detector IceCube. Crédito: Nicolle R. Fuller, IceCube/NSF

A diferencia de la luz, los neutrinos pueden escapar en grandes cantidades de entornos altamente densos en el universo y llegar a la Tierra sin ser perturbados por la materia y los campos electromagnéticos que impregnan el espacio extragaláctico. Aunque los científicos concibieron la astronomía de neutrinos hace más de 60 años, la débil interacción de los neutrinos con la materia y la radiación los hace extremadamente difíciles de detectar. Los neutrinos podrían ser clave para nuestras preguntas sobre cómo funcionan los objetos más extremos del universo.

«Responder a estas preguntas de gran alcance sobre el universo en el que vivimos es un enfoque principal de la Fundación Nacional de Ciencias de EE. UU.», dice Dennis Caldwell, director del Departamento de Física de la Fundación Nacional de Ciencias de EE. UU.

Este video muestra cómo los neutrinos de IceCube nos dieron nuestro primer vistazo a las profundidades internas de la galaxia activa, NGC 1068. Crédito: Video de Diogo da Cruz, con la voz de Falun Mayanga y Georgia Kao.

Al igual que con nuestra galaxia de origen, el[{» attribute=»»>Milky Way, NGC 1068 is a barred spiral galaxy, with loosely wound arms and a relatively small central bulge. However, unlike the Milky Way, NGC 1068 is an active galaxy where most radiation is not produced by stars but due to material falling into a black hole millions of times more massive than our Sun and even more massive than the inactive black hole in the center of our galaxy.

NGC 1068 is an active galaxy—a Seyfert II type in particular—seen from Earth at an angle that obscures its central region where the black hole is located. In a Seyfert II galaxy, a torus of nuclear dust obscures most of the high-energy radiation produced by the dense mass of gas and particles that slowly spiral inward toward the center of the galaxy.

Messier 77 and Cetus in the sky. Credit: Jack Parin, IceCube/NSF; NASA/ESA/A. van der Hoeven (insert)

“Recent models of the black hole environments in these objects suggest that gas, dust, and radiation should block the gamma rays that would otherwise accompany the neutrinos,” says Hans Niederhausen, a postdoctoral associate at Michigan State University and one of the main analyzers of the paper. “This neutrino detection from the core of NGC 1068 will improve our understanding of the environments around supermassive black holes.”

NGC 1068 could become a standard candle for future neutrino telescopes, according to Theo Glauch, a postdoctoral associate at the Technical University of Munich (TUM), in Germany, and another main analyzer.

IceCube detector schematic showing the layout of the strings across the ice cap at the South Pole, and the active detection array of light sensors filling a cubic kilometer volume of deep ice.

“It is already a very well-studied object for astronomers, and neutrinos will allow us to see this galaxy in a totally different way. A new view will certainly bring new insights,” says Glauch.

These findings represent a significant improvement on a prior study on NGC 1068 published in 2020, according to Ignacio Taboada, a physics professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology and the spokesperson of the IceCube Collaboration.

From left to right: Martin Wolf (TUM), Hans Niederhausen (TUM), Elisa Resconi (TUM), Chiara Bellenghi (TUM), Francis Halzen (UW–Madison), and Tomas Kontrimas (TUM). Credit: Yuya Makino, IceCube/NSF

“Part of this improvement came from enhanced techniques and part from a careful update of the detector calibration,” says Taboada. “Work by the detector operations and calibrations teams enabled better neutrino directional reconstructions to precisely pinpoint NGC 1068 and enable this observation. Resolving this source was made possible through enhanced techniques and refined calibrations, an outcome of the IceCube Collaboration’s hard work.”

The improved analysis points the way toward superior neutrino observatories that are already in the works.

“It is great news for the future of our field,” says Marek Kowalski, an IceCube collaborator and senior scientist at Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron, in Germany. “It means that with a new generation of more sensitive detectors there will be much to discover. The future IceCube-Gen2 observatory could not only detect many more of these extreme particle accelerators but would also allow their study at even higher energies. It’s as if IceCube handed us a map to a treasure trove.”

The IceCube Collaboration, spring 2022. Credit: IceCube Collaboration

With the neutrino measurements of TXS 0506+056 and NGC 1068, IceCube is one step closer to answering the century-old question of the origin of cosmic rays. Additionally, these results imply that there may be many more similar objects in the universe yet to be identified.

“The unveiling of the obscured universe has just started, and neutrinos are set to lead a new era of discovery in astronomy,” says Elisa Resconi, a professor of physics at TUM and another main analyzer.

“Several years ago, NSF initiated an ambitious project to expand our understanding of the universe by combining established capabilities in optical and radio astronomy with new abilities to detect and measure phenomena like neutrinos and gravitational waves,” says Caldwell. “The IceCube Neutrino Observatory’s identification of a neighboring galaxy as a cosmic source of neutrinos is just the beginning of this new and exciting field that promises insights into the undiscovered power of massive black holes and other fundamental properties of the universe.”

Reference: “Evidence for neutrino emission from the nearby active galaxy NGC 1068” by IceCube Collaboration, R. Abbasi, M. Ackermann, J. Adams, J. A. Aguilar, M. Ahlers, M. Ahrens, J. M. Alameddine, C. Alispach, A. A. Alves, N. M. Amin, K. Andeen, T. Anderson, G. Anton, C. Argüelles, Y. Ashida, S. Axani, X. Bai, A. Balagopal V., A. Barbano, S. W. Barwick, B. Bastian, V. Basu, S. Baur, R. Bay, J. J. Beatty, K.-H. Becker, J. Becker Tjus, C. Bellenghi, S. BenZvi, D. Berley, E. Bernardini, D. Z. Besson, G. Binder, D. Bindig, E. Blaufuss, S. Blot, M. Boddenberg, F. Bontempo, J. Borowka, S. Böser, O. Botner, J. Böttcher, E. Bourbeau, F. Bradascio, J. Braun, B. Brinson, S. Bron, J. Brostean-Kaiser, S. Browne, A. Burgman, R. T. Burley, R. S. Busse, M. A. Campana, E. G. Carnie-Bronca, C. Chen, Z. Chen, D. Chirkin, K. Choi, B. A. Clark, K. Clark, L. Classen, A. Coleman, G. H. Collin, J. M. Conrad, P. Coppin, P. Correa, D. F. Cowen, R. Cross, C. Dappen, P. Dave, C. De Clercq, J. J. DeLaunay, D. Delgado López, H. Dembinski, K. Deoskar, A. Desai, P. Desiati, K. D. de Vries, G. de Wasseige, M. de With, T. DeYoung, A. Diaz, J. C. Díaz-Vélez, M. Dittmer, H. Dujmovic, M. Dunkman, M. A. DuVernois, E. Dvorak, T. Ehrhardt, P. Eller, R. Engel, H. Erpenbeck, J. Evans, P. A. Evenson, K. L. Fan, A. R. Fazely, A. Fedynitch, N. Feigl, S. Fiedlschuster, A. T. Fienberg, K. Filimonov, C. Finley, L. Fischer, D. Fox, A. Franckowiak, E. Friedman, A. Fritz, P. Fürst, T. K. Gaisser, J. Gallagher, E. Ganster, A. Garcia, S. Garrappa, L. Gerhardt, A. Ghadimi, C. Glaser, T. Glauch, T. Glüsenkamp, A. Goldschmidt, J. G. Gonzalez, S. Goswami, D. Grant, T. Grégoire, S. Griswold, C. Günther, P. Gutjahr, C. Haack, A. Hallgren, R. Halliday, L. Halve, F. Halzen, M. Ha Minh, K. Hanson, J. Hardin, A. A. Harnisch, A. Haungs, D. Hebecker, K. Helbing, F. Henningsen, E. C. Hettinger, S. Hickford, J. Hignight, C. Hill, G. C. Hill, K. D. Hoffman, R. Hoffmann, B. Hokanson-Fasig, K. Hoshina, F. Huang, M. Huber, T. Huber, K. Hultqvist, M. Hünnefeld, R. Hussain, K. Hymon, S. In, N. Iovine, A. Ishihara, M. Jansson, G. S. Japaridze, M. Jeong, M. Jin, B. J. P. Jones, … J. P. Yanez, S. Yoshida, S. Yu, T. Yuan, Z. Zhang, P. Zhelnin, 3 November 2022, Science.

DOI: 10.1126/science.abg3395

The IceCube Neutrino Observatory is funded and operated primarily through an award from the National Science Foundation to the University of Wisconsin–Madison (OPP-2042807 and PHY-1913607). The IceCube Collaboration, with over 350 scientists in 58 institutions from around the world, runs an extensive scientific program that has established the foundations of neutrino astronomy.

«Alborotador. Amante de la cerveza. Total aficionado al alcohol. Sutilmente encantador adicto a los zombis. Ninja de twitter de toda la vida».

More Stories

Formación de formadores expertos en Libia – IARC

TESS encuentra su primer planeta rebelde

Los médicos combinaron una bomba cardíaca y un trasplante de riñón de cerdo en una cirugía avanzada